The study of landscapes, their attributes, and origins is the primary interest of geologists. This sub-discipline of geology is known as geomorphology. This involves the study of Earth’s surficial processes and their results.

Students in Hocking College’s GeoEnvironmental Science Program recently examined a variety of landforms along the Hocking River Valley. Many of these landscape features were formed by processes or events that are no longer occurring in this region. Their origins are pieces in the puzzle that is the geologic history of Southeastern Ohio. More practically, some of the landforms in the valley consist of distinctive type of deposits that in some cases are valuable resources, such as the sand and gravel deposits of stream terraces along the valley. In other cases, the deposits of a landform in the Hocking River Valley present engineering problems and hazards such as landslides. Students from the GeoEnvironmental Science Program at Hocking College.

Students from the GeoEnvironmental Science Program at Hocking College.

Complex landscapes like the hilly Appalachian Plateau region of Southeastern Ohio record many past geologic events that modified the Earth’s surface. Deciphering some of these events and their results enriches our understanding of this unique region, but also has practical applications.

It's common to assume that in hilly regions such as Southeastern Ohio rivers flow in the valleys they carved into the local bedrock. This simple assumption seems reasonable when we consider how a landscape consisting of hills and valleys arrived at its present configuration. However, landscapes evolve over long periods of time and their present configurations are the results of the imprints left on them by many past geologic events. The relationship of a river to the valley it flows through can be very complex. Such is the case for the Hocking River of Southeastern Ohio.

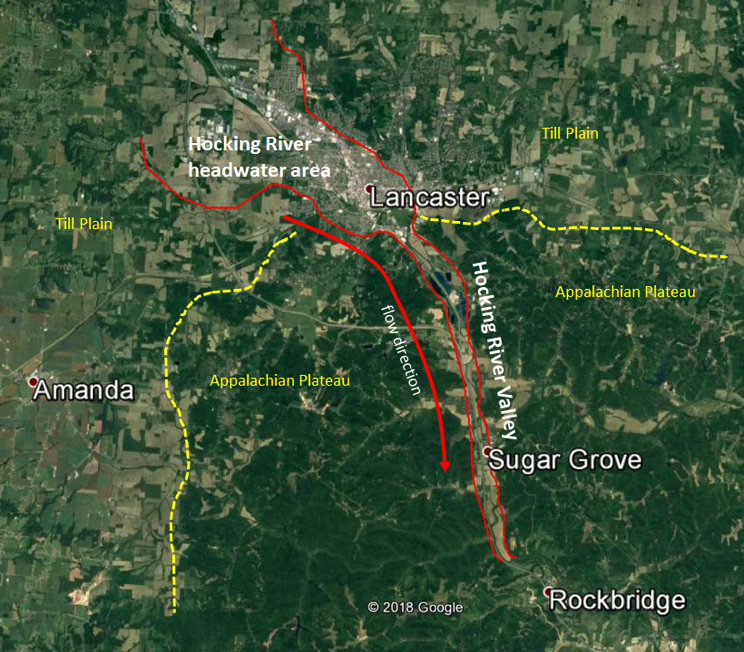

It's most typical for rivers to flow from elevated hilly areas (foothills) on to adjacent lower-lying plains. At Earth’s surface, water runs downhill and the landscape generally slopes downhill from hilly areas to plains. However, the Hocking River draws its headwaters from the rolling plains north of Lancaster and flows southeastward toward the higher elevation foothills of the Appalachian Plateau. Here it enters a narrow valley carved into the local bedrock (pictured below). Contrary to the common assumption, the modern Hocking River did not carve the valley in which it now flows.

The Hocking River Valley in the Lancaster-Sugar Grove area. Note, the valley widens to the north, whereas the present flow direction is to the south.

The Hocking River Valley in the Lancaster-Sugar Grove area. Note, the valley widens to the north, whereas the present flow direction is to the south.

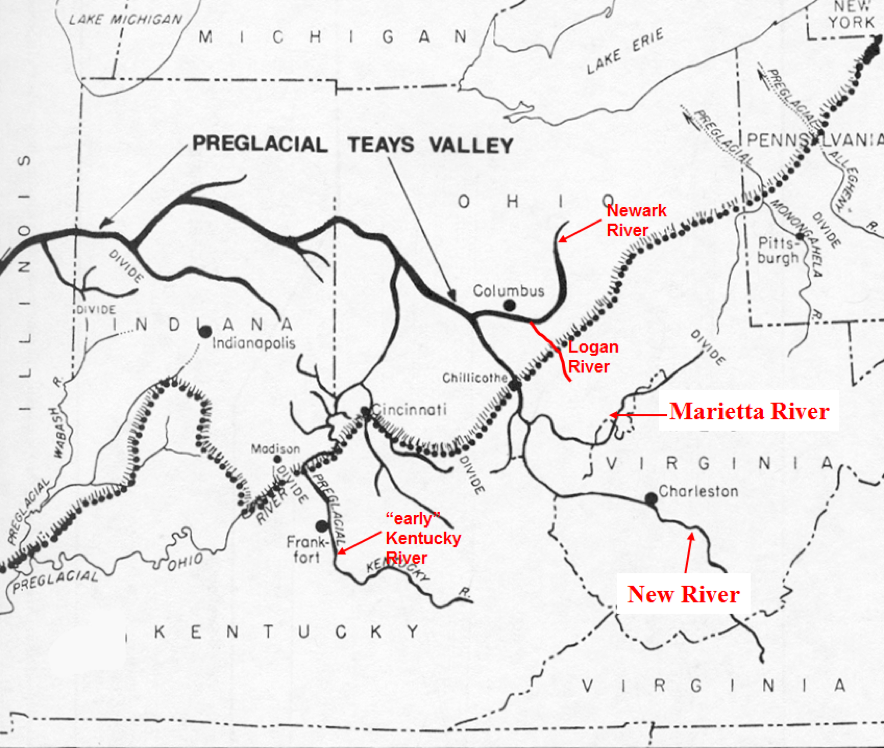

These geomorphic events, which lead to the formation of the valley in which the Hocking River flows today, can be traced back to Teays Stage of the Pleistocene Epoch. This time interval includes the several ice ages that impacted North America and Ohio. It began about 1.6 million years ago and ended about 10,000 years ago. Ohio’s landscape, particularly the river systems, was configured very differently than today. Indeed, at the onset of the Pleistocene Epoch neither the Ohio River, Scioto River, Miami River, Muskingum River, nor the Hocking River existed. In their place was a major north-flowing river, the Teays River, and lesser known tributaries such as the Newark and Marietta Rivers. This early part of the Pleistocene Epoch, before Ohio’s first ice age, is known as the Teays Stage. During the Pleistocene Epoch and before about 500,000 years ago, glacial ice spread southward from Ontario, across northern Ohio, and terminated just south of Lancaster, OH near the edge of the Appalachian Plateau (pictured below). At that time, the area where the modern Hocking River valley now lies was occupied by the north-flowing Logan River, a tributary of the Newark, which in turn was a tributary of the well know Teays River.

Paleogeography of the Teays River and its major tributaries in Ohio, including north-flowing Logan River. Note the dotted line showing the maximum extent of the glacier that dammed the valleys of the Teays and Logan Rivers.

Paleogeography of the Teays River and its major tributaries in Ohio, including north-flowing Logan River. Note the dotted line showing the maximum extent of the glacier that dammed the valleys of the Teays and Logan Rivers.

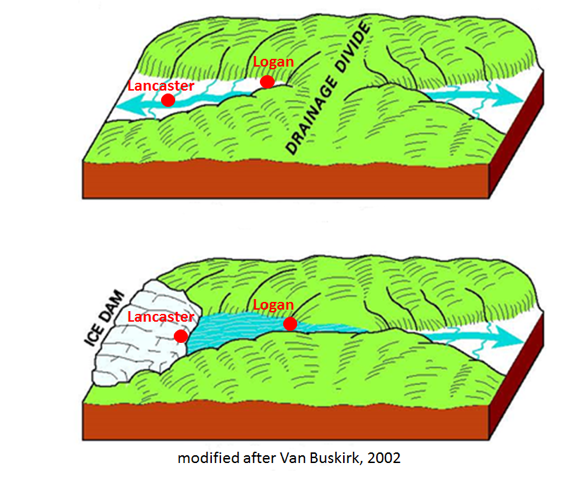

As glacial ice reached its maximum extent south of Lancaster, it formed a massive ice dam across the valley of the north-flowing Logan River. The ice-dam ponded the waters of the Logan River producing a lake whose waters extend all the way up the river valley to the drainage divide that lay south of the town of Logan. These types of lakes are known as pro-glacial lakes for their position at the “front” of glaciers (pictured below).

Model shows formation of pro-glacial lake in Logan River Valley by glacial-ice dam.

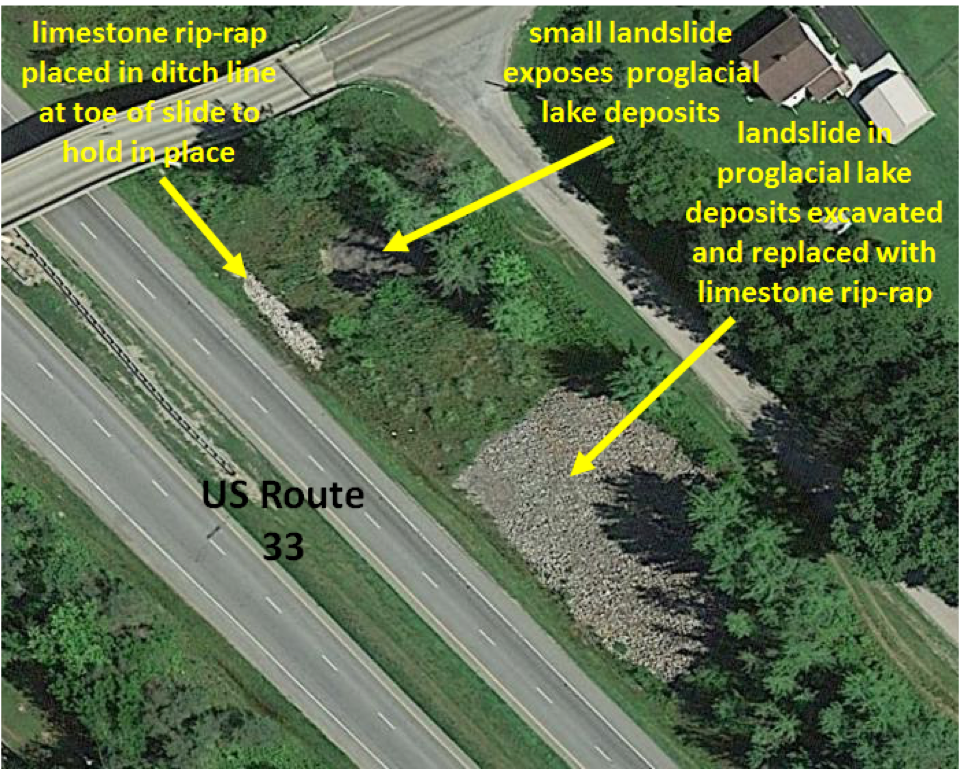

Geologists think a pro-glacial lake that formed in the Logan River valley was present for at least several thousand years until the glacier retreated back into Canada. Thin layers of sediment, salt, and clay accumulated on the lake bottom during this time. Remnants of these lake-bottom sediments are still preserved along a portion of the old Logan River valley (pictured below).

Thinly layered salt and clay lake-bottom sediments preserved along a portion of

Thinly layered salt and clay lake-bottom sediments preserved along a portion of

theold Logan River Valley State Route 664 exit at Logan, OH.

Lake-bottom sediments that accumulated on the bottom of the pro-glacial lake in the Logan River valley are present today along both sides of U.S. Route 33, just south of the State Route 664 exit at Logan, OH. They are present in the grassed slopes excavated during highway construction. These soft, weak, clayey lake-bottom deposits can cause engineering problems as they are prone to producing small landslides. The Ohio Department of Transportation remediates such landslides by excavating the slide material and replacing it with large limestone boulders which will help stabilize the slope (pictured below).

Small local landslides formed in lake-bottom sediments of former pro-glacial lake

in ancient Logan River Valley.

For more information on Hocking College’s GeoEnvironmental Science Program, contact Kimberly Caudill at caudillk7007@hocking.edu or (740) 753-6303, or contact Michael Caudill at caudillm@hocking.edu or (740) 753-6277.