NELSONVILLE, Ohio — It was a beautiful winter’s day in early 2020. Snow covered the trails at Conkle’s Hollow State Nature Preserve, as icicles shimmed in the sunlight.

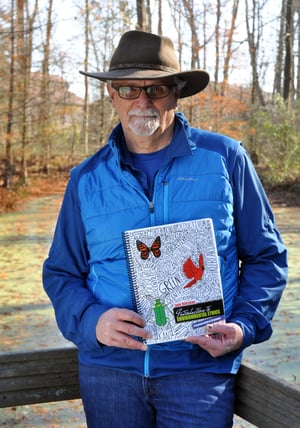

A man walking the trails walked up to Lynn Holtzman, Hocking College’s Wildlife Resources Management program manager, and grabbed his hand to shake it.

“He said, ‘Congratulations! You have these kids reading Thoreau. I can’t believe they’re out here reading Thoreau,’” Holtzman remembered the man saying of his environmental ethics students.

“He said, ‘Congratulations! You have these kids reading Thoreau. I can’t believe they’re out here reading Thoreau,’” Holtzman remembered the man saying of his environmental ethics students.

Holtzman recalled his response, “Where else would you read Thoreau?”

“I have a lot of strange ways of teaching environmental ethics,” he said after sharing the Conkle’s Hollow story.

Holtzman developed Hocking College’s environmental ethics class ten years ago and has taught it ever since.

Until this year he would photocopy the readings for his students and hand them out in class.

Now he’s written a book to help guide his students through the course and potentially give instructors and their students at other institutions a guide to the topic.

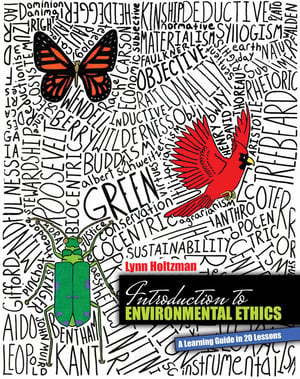

The book — “Introduction to Environmental Ethics: A Learning Guide in 20 Lessons” — is a collection of readings, lesson outlines and tear-out student exercise sheets.

He’s incorporated many of the lessons he’s developed over the years into the book, published in August by Kendall Hunt Publishing Company in Dubuque, Iowa.

Now with the readings all collected in one place and with the tear-out sheets Dr. Daniel Kelley believes the book is poised to become the perfect “canned” tool for instructors across the country.

“This is a first of its kind book,” Kelley, dean of the School of Natural Resources at Hocking, said. “This is a topic that a lot of people find important and find a way to teach. However, there is no good ‘go-to’ widely used book. I think Lynn’s book could quickly become that.”

Holtzman presents the class in a way that teaches students how to apply the environmental ethic they already have.

“Many students who come into this class already have a land ethic or a natural resources ethic, or they wouldn’t be here,” he explained. “They want to make a profession out of it.”

A big part of Holtzman’s class and book deal with students examining why they’re studying natural resources, what ethics they have and what experiences brought them to those beliefs and places.

For Holtzman personally, who spent 30 working for the Ohio Department of Natural Resources Division of Wildlife before spending the last decade teaching, there were two instances that stand out.

“The reason I’ve spent 40 years working in the natural resources field is because my grandfather had a place in the upper peninsula of Michigan,” he said “I went there every summer and I just developed a love for the natural world through fishing and hiking through the north woods.”

He credits the love for nature that was passed down from generation to generation in his family before it even got to him as part of the reason he’s spent so much time working in natural resources.

“Thoreau and Leopold believed that ethics is developed experientially,” he said. “That people who come in contact with nature begin to develop a passion, love and affection for nature that really ends up being an ethic.”

The second reason came while he was a student at Hocking College.

The second reason came while he was a student at Hocking College.

At the beginning of his second year he had the opportunity to take over his grandfather’s cabinet business.

It was an opportunity to walk into a successful business, one he was already familiar with, but it would mean leaving college and not pursuing a career in natural resources.

He went to a trusted professor to talk about his two options. The professor told him to read Aldo Leopold’s “A Sand County Almanac.” A collection of essays describing the land around Leopold’s Wisconsin home, the book is considered a landmark in the American conservation movement.

“Leopold probably influenced me more than anyone else in my thinking and ethics,” Holtzman said. And reading it that first time convinced him to stay in school and pursue a career in natural resources. And most likely, he will end his professional career where he started it, at Hocking College.

Teaching Applied Ethics

“I’m an applied science guy so I’m an applied ethics guy,” Holtzman said.

He wants students to be able to look at theories and be able to think critically about them, but also see how they can be applied to their life and career.

“It’s nice to be able to think of the metaphysics of Aristotle and Emmanuel Kant,” he said. “But I want the students to be able to get excited about what they’re reading and learn from what they're reading.”

Most of his students have never taken a philosophy or ethics course before.

To help make the subject more accessible he includes elements from popular culture like the movie “Avatar,” fiction like “The Bear” by William Faulkner, as well as writing from Leopold, Henry David Thoreau and John Muir, people you’d expect to find in an environmental ethics text.

“Martin Luther King Jr.’s Letter from a Birmingham Jail is in there," Holtzman said. “I believe he, more than anyone, articulates what an unjust law is and when you need to protest and how you need to protest. You certainly can apply his principles to environmental activism.”

He also gives them examples from his decades in the field of how to talk to people who have different environmental ethics than they do.

He tells stories of trying to talk farmers in western Ohio into changing the farming habits passed down from generation to generation in order to save their soil and water quality, and talking to an animal rights activist dressed in a blood-covered dove costume protesting against the first dove season at a public hunting area.

But mainly it’s about getting his students to think and be able to discuss why they think the way they do and to understand and respect that others may think differently than them.

But mainly it’s about getting his students to think and be able to discuss why they think the way they do and to understand and respect that others may think differently than them.

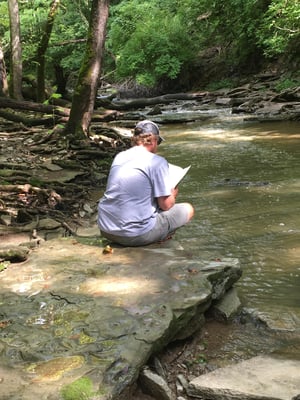

On the same winter’s day that he was congratulated for getting students to read Thoreau’s essay “Walking,” it was getting time for the class to return to campus.

One group hadn’t returned to the trail head. Fearing something may have happened to them Hotlzman set out to find them.

“I got to the lower trail and they were just there sitting and talking about Thoreau and what they’d been reading,” Holtzman recalled. “I said to myself, ‘O.K. Cool.’”

Because really what better place is there to develop your environmental ethic than a walk in the woods?

More about the Wildlife Resources Management Degree Program at Hocking College

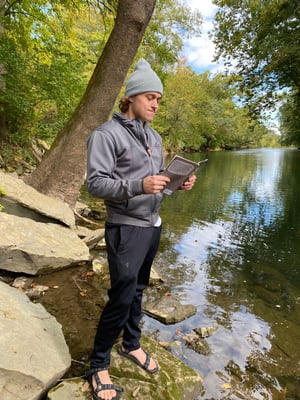

The Wildlife program at Hocking College is a hands-on, experience-based curriculum. Students actively learn and practice field skills here that they will only hear about in other more traditional wildlife management programs.

Students leave the program with a strong conceptual understanding of wildlife management, ecology, and conservation, as well as botany and plant ecology and identification, and natural resources as a whole.

Skills learned include wildlife, fish and plant field and lab identification; wildlife field data collection techniques such as survey, capture, radio telemetry, habitat and population sampling; and other general field skills such as map reading, watercraft operation and natural resources equipment operation.

The Wildlife Resources Management degree is designed for students interested primarily in seeking employment in fish and wildlife careers after acquiring their two-year associate degree. Most positions with Ohio county and state parks, and the Ohio Division of Wildlife, require a two-year wildlife degree.

For more information contact Wildlife Resources Management Program Manager Lynn Holtzman at holtmanl@hocking.edu or 740-753-6274.